BAR X | Eau Pernice & Alexander Brix Tillegren | Photo: Jakob Boserup

Manuscript for a reading at Art Hub Copenhagen. Translated from Danish by Jennifer Russell

To begin with, I should say that this is a translation. My mother tongue is Danish, and when I switch to English, I find myself saying and thinking something other than I would have in Danish. The reality I construct through my words radically changes between the two languages. That also means that this is not the original text; a translator has read my Danish words closely, and with great care she has put in my mouth the English words I am now speaking. Some of what I am saying I might not have known what meant had I heard it.

I will be presenting a collection of notes, anecdotes and coincidences relating to a project that has gripped me for the past nine years, and which I will give the overarching title tonoton. In addition to words, the project encompasses two groups of sculptures and a graphic print.

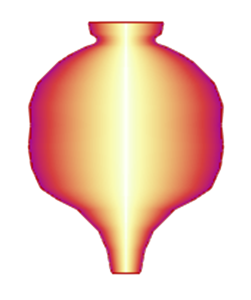

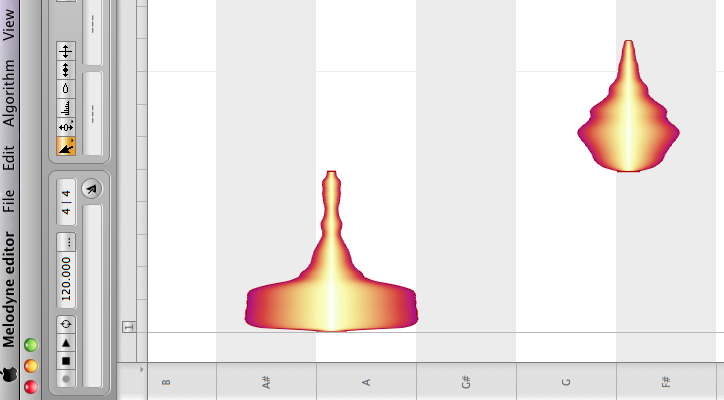

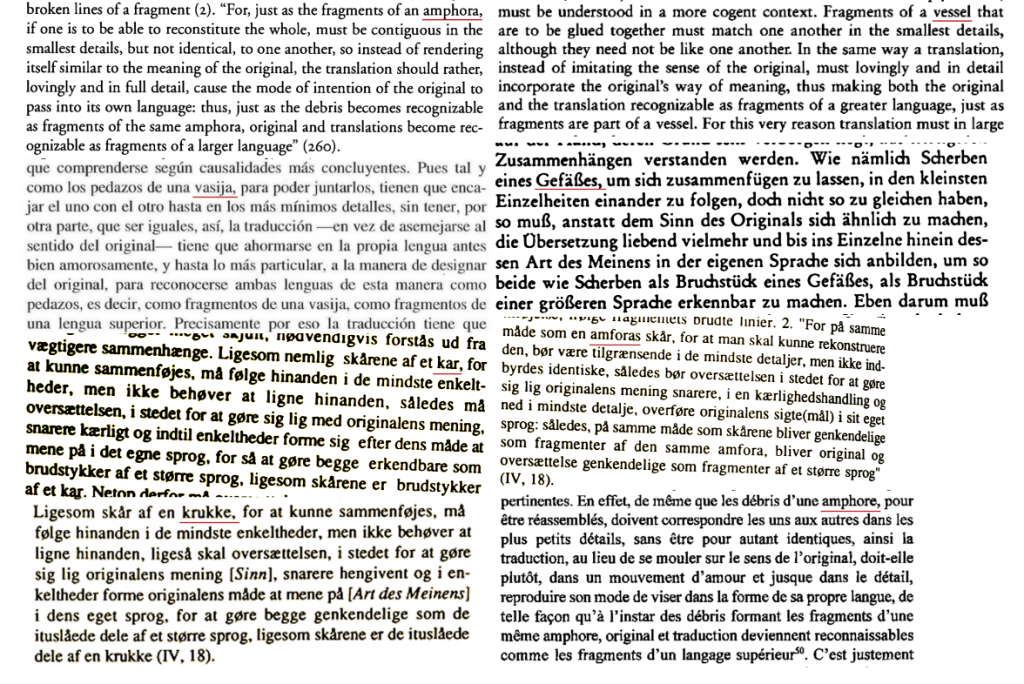

I am interested in language, and particularly in the spoken word, the tone, which can change both the meaning of the word and the space in which it is spoken, the relation between speaker and receiver. A friend introduced me to an audio software called Melodyne which you can use to change the melody of a voice recording. Spoken words are represented as sound waves with an even, unbroken contour in shimmering hues of red, creating the illusion of mass. If you rotate the sound-images 90 degrees, the words look like vases.

A rotated screenshot of the word ‘amphora’ pronounced and recorded by Melodyne

There’s a video – it appears to be a digitalised VHS tape from a therapy session – in which a man is asked a number of questions. The man, who suffers from Broca’s aphasia as a result of a stroke, can say only one thing: tono tono. But because the intonations of his original language remain intact, I just about understand him. I’ve read that it’s common for people with aphasia to express themselves through meaningless two-syllable sounds. Tono tono appears among the examples. His language is broken, and tone is his means of expression.

In City of Glass by Paul Auster, a man walks around collecting broken objects. The world has changed, but language has remained the same, and words therefore no longer correspond to their objects. Language breaks down when the world does, and vice versa. The novel is written in English, and I read translations of it in the languages I understand. It seems reasonable enough that a fabricless umbrella is no longer an umbrella, but only in the Spanish translation does a direct connection between the object’s name and function reveal itself. In Spanish, an umbrella is a ’paraguas’ – literally ’against water’. Obviously, an against-water that does not keep you dry must be given a different name.

Translating a text is like gluing a broken vase: the edges of the fragments must fit together precisely, but the shards themselves need not necessarily be alike. I try to rephrase this excerpt from Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Task of the Translator’ in my own words to understand what it means. I’m unsuccessful, so I consult other translations of the same text. But I forget what I am looking for, because in each translation the vase shapeshifts before my eyes. It becomes a vessel, then a jar. A basin and an amphora.

I feel compelled to express this observation of the translator’s transformation of the object, but it feels mundane, and I can’t think of any brilliant idea for how to turn it into an artwork. This happens to coincide with a course in silkscreen printing, so I end up printing the text on transparent bags. Afterwards, I put the bags in a moving box of things I’m not yet ready to throw out, and they remain in limbo at my parents’ house, awaiting a final verdict. My mother has a substantial berry production and discovers a posthumous function for the bags: as containers for freezing her summer harvest. The temperature causes the paint on the bags to react and the letters peel off. When she opens the freezer at the end of the season, Walter Benjamin’s words are stuck to its sides and interior compartments, but they’ve been scrambled and now form new sentences out of words in various languages.

I give a reading of this text in Århus, and an audience member tells me about the carrier bag theory of human development and its implications for fiction. Hunters brought home meat, and along with it, dramatic tales of peril and heroism. Meanwhile, something else, discreet and constant, kept the community supplied with a store of gathered foods: the container. The bag, it is proposed, came before the weapon. How would the classic narratives change if the essentialness of the container were recognised in the history of human development? The Danish word for container, pronounced in English, is ‘beholder’. An observer, a recipient of information which can be stored within it.

Saying words, seeing their sound-images and discovering that the sound-images look like vases prompts me to examine the relationship between term and object. What word for vase most resembles a vase? Vase itself is too ambiguous, I try amphora. Its sound-image is two vases, one bottom-heavy with a long neck, the other plump with a narrow mouth. This is amphora, and so the image of an elongated, Greek vessel I have in my head needs another name.

How do you make a vase if not through spoken words and sound-images? It’s harder done than said, throwing clay. My pottery teacher is patient – unlike me. I check the label on the pack of clay; there must be something wrong with it. ‘German red clay. Ton,’ it says.

In German, clay is called Ton. And Ton also means sound in German. A tonne is a unit of measure. In addition to being a cylindrical container, in Danish, a tønde, or barrel, is a Scandinavian unit of area, from Medieval Latin tunna, meaning wine cask. It exists in English as a tun, a unit of liquid volume. Tuna, or tunny, is a fish, from Old Provençal ton. In Italian, tonno.

I listen to Danish radio while cooking in my kitchen in Vilnius, just to hear my own language. I’m only half-listening to the sentences that fly by me, but suddenly something registers. A man robbed a woman at a supermarket in central Jutland, threatening her with a mackerel while saying ‘tuna tuna’.

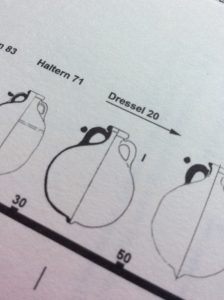

Several years go by before I examine what sound-image the word Ton makes. It materialises on screen as a round vase with a pointed base. I’m living in Germany and read about the amphorae discovered by archaeologist Heinrich Dressel in Italy. And there it is. He archived it as Dressel 20, but I know, because I’ve said it out loud and seen it: its name is Ton.

From the balcony of the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, I look down at a small lorry in a car park below. Painted onto the asphalt is an ornamental pattern which may have a practical function I cannot discern from above. It reminds me of something. Back when I first started my studies, I would imagine existing artworks inserted into various contexts and reflect on what kinds of meaning it might give rise to. On the bus one day, I emailed a fellow student presenting one of these imagined exhibitions as his curatorial work and asked him about the thinking behind it. Parts of the Pergamon Altar had been installed inside a lorry that shuttled back and forth between Berlin and Athens. I had been fortunate enough to see the exhibition at a rest stop south of Nuremberg, I told him.

Hi Eau, thanks for your note.

It’s always nice when one’s exhibitions get people thinking. For me, it’s interesting to ask what thoughts I did not have. I work with a curatorial peel-back method in which I peel away ideas from my thoughts until I’m left with the essential building blocks for the given exhibition. In this case, Greek ornament and Scandinavian freight transport. I’ve always been fascinated by E45, Europe’s coronary artery, and the gesture inherent in the exchange of goods between north and south. It’s a beautiful thought, this connecting link between cultures. Our friends in Greece who made the Pergamon Altar also invented Ouzo, and some historians believe that the story of Jesus turning water into wine in fact comes from the Phoenicians’ first encounter with the Greeks’ Ouzo, which is, of course, a clear spirit until mixed with water, upon which it suddenly acquires colour. With that in mind, I found it important to show how trade routes between cultures have always built bridges between the inner lives of the respective peoples.

The E in E45 stands for Empathy.

In their theory of metaphor, philosopher Mark Johnson and linguist George Lakoff describe how containers are used as metaphors in our everyday language. Our physical perception of being in a space is connected to our emotional life and relations. The word ‘in’ does not change, whether we are in the bath, in a relationship or fall in love with someone. The relationship is a vessel. You’re in it. What’s in it for me?

I am made aware of an old English gender-neutral pronoun, and at this point I don’t think it will come as any surprise when I say that the pronoun is thon, a contraction of ‘that one’.

Metaphorical clichés are often used to describe a relationship as a fragile entity. Crumbling, shattering, patching things up. Language shapes how we understand causality and responsibility. Whereas in English you would say, ‘Signe broke the vase,’ even if it was an accident, in Spanish you say that the vase broke itself. A relationship broke one winter day in Florence. Several years later in Copenhagen, we’re reunited. Ever since, a loose connection across national borders. We are a glued vase; the shards are alike, but their edges don’t align. The cracks are on the surface, a visible web of dark lines. Traces of the damage already done and a reminder of the consequence of new blows. I had never met anyone who, like me, moves regularly between places, stories and coincidences, trying to piece together a fundament of meaning to tell a different story. Until Thon.

The Dressel 20 amphora, that is, ton, was discovered in Rome at Monte dei Cocci, the mountain of pottery shards; an accumulation of pots sailed to Rome from other parts of the Roman Empire and subsequently emptied and shattered. A mountain of the broken word TON that seems to connect language, material and trade. Thon wants to come along to see the mound, and we arrange to meet in Rome after Easter.

Soft Italian words flow out of thons mouth like notes, Thon gesticulates so I understand a little. The Italian woman we’re with understands everything. When we meet in Italy, my metaphorical ideas turn into concrete action, and Thon knows what to do. There’s a cocktail bar with mirrors on the walls, and this woman from Calabria knows someone who can help us access Monte dei Cocci. Yesterday, we walked around the mountain. A steep base of stacked shards, 53 million broken pots, a tall fence surrounding the entire hill, one kilometre in circumference. With the help of the woman at the bar, a dinner with three solicitors is arranged.

A restaurant with a heavy wooden door, thick, dark-green paint. It’s hard to open and slams behind you, thrusting you into the restaurant. Hefty noise level. We sit at a round table with a white tablecloth to the right of the entrance. The table is big for five people, so we sit far apart. I take a seat at the periphery, close to Thon, and Thon knows to raise thons voice loudly like the Italian solicitors do. They meet in the middle, circle around the subject as they eat, and finally it is arranged that a tour will take place at Monte dei Cocci the following day. We drink limoncello and eat sugary cake.

From the tram, we see a banner at Complesso del Vittoriano advertising an exhibition by the painter Giorgio Morandi. He painted vases. We walk through the exhibition at each our own pace. I could tilt my head to the side and imagine which words the shapes of the painted vases might contain. Linguistically decipherable still lifes.

A guide tells us about the mountain’s history, Thon translates. We’re familiar with the story, and now it changes. This is a mountain of fragmented words, and they can be given new meaning. Left on our own, we wrap up various shards in fabric and stuff them into my backpack. I bring them back to Leipzig where I 3D scan them, alter the files by adding inscriptions to the surface: text fragments about the origins of language, Ton is the Word, and I add my own name, for the archaeologists and art historians of posterity. The shards are returned to Monte dei Cocci.

For the future’s archeologists and art historians, Eau Pernice. 2019 – 2020. 3D-printed clay, bisc fired. Variable dimensions

We need to talk. In Berlin. Each day, we repair the words, one by one. We write texts, read them aloud to one another, write down what we heard and talk about why we hear something other than what was said. Things are better now. We go for runs in the neighbourhood, point and speak. We stop by an exhibition opening, drink wine, drift along with the crowd to a bar. We have to rein it in, the place is run by an elderly couple, there’s no music. A long table, animated conversations across it. The tone alternates between rowdy and formal. The inevitable question: So what do you do? This time I’m prepared, I have this whole text in my head, and it’s just a matter of deciding where to start. I’m repairing language, I say, but regret the pretentious opening. It all started when I saw a video of a man who could only say tono. Europe is connected in the word Ton: containers transporting information across borders and time. The word is part of a simple and universal language we have broken. The conversations ebb out. I look at Thon, who looks down at the table. I fall out of step, try to catch up to the rhythm. Ton means sound and clay. And tone and tonne and tuna. And tono tono, tono tono tono.